Of all the Blacks killed by the Detroit Police and National Guard, only one man, Jack Sydnor, 38, was killed in a direct exchange of gun fire. He was shot after firing on Officer Roger Poike from a third floor window. This suggest that for the dozens of sniper attacks initiated by the insurgents, they demonstrated a high level of skill and determination to have survived the firefights. It would not be surprising if many of the sniper teams and individuals were Black Vietnam Veterans. That would be ironic, considering the after hours party at the "blind pig" raided by the Detroit Police on July 23, was a welcome home party for two Black Vietnam Vets.

Often underreported are the casualties inflicted by the insurgency on the state. The numbers go to the heart of the rising's insurrectionary character. One Detroit Police Officer and one National Guardsman was killed, along with two City of Detroit Firemen. Not a single law enforcement officer or National Guardsman was killed in the 92' Los Angeles revolt.

Among the combined force of the Detroit Police, Michigan State Police, the National Guard and U.S. Armed Forces, over 478 people were injured. Thus, 26% of the 1,889 people harmed during the rising, were forces of the state. One other point should be made regarding the "violence" during the revolt. In that five-day period, there was not one report filed of a "Black-on-Black" murder in Detroit--a rather astonishing fact considering a "lawless mob" often controlled the streets.

Making the argument that Detroit 67 was an urban insurrection--the only one of its kind in American history--is to go against the grain. However, the statistics presented here demonstrate the insurgent character of the rising as much as its scale. The attempt to obliterate its revolutionary character is encapsulated in the standard "by the numbers" analysis of the Detroit rising.

That narrative of the Detroit 67' proceeds as follows; 43 people died, over 1800 people were injured, 7000 people were arrested and over 2,000 buildings with an estimated property loss of $40 million were destroyed. The Detroit "riot" was the third worst riot in American history, after the New York City "Draft Riot" of 1863 (121 killed), and the 1992 Los Angeles "Rodney King Riots (60 killed)." These analyses define Detroit as a depoliticized riot, measured by dry statistics, and devoid of political content.

The New York City "Draft Riots" of 1863 was largely a revolt by working-class Irishmen against Congressional draft laws passed that pressed them into service in the Civil War. Irishmen, feared losing their jobs to Blacks in the city, while fighting a war to end slavery. They didn't want to do either. Their revolt against the draft, turned immediately into a murderous racial rampage against New York City's local Black population. Ultimately, President Lincoln was forced to dispatch troops from Gettysburg to restore order. New York City didn't have a race riot; it had a pogrom against Black people.

The Los Angeles revolt was America's first modern multi-racial rising. Anger at the acquittal of Los Angeles police in the Rodney King beating unleashed a furor across the city. A third of those killed and half of those arrested were Latino. There was significant Korean participation, and a lot of whites leveraged the moment to do some looting and vandalism of their own. More people were killed by store owners defending their properties, than by law enforcement.

Los Angeles was never a frontal assault against the "Tower" (government and law enforcement). The outrage at American justice was much more focused on looting and property destruction. Black, Korean, and Hispanic businesses took heavy losses. In Detroit, many Black businessmen painted the words "Soul Brother" on their storefronts to avoid the fury of the rising. The historic Motown Records building, located at ground zero of the revolt, was never touched. In Los Angeles, law enforcement did not so much attempt to crush the rising, as contain it and gradually allow it to "burn out."

On the 50th Anniversary of Detroit 67, hundreds of newspaper articles were written, and a major picture (Detroit) was released. Panel discussions were convened on national television. This revisiting was a profound statement about the importance of locating Detroit 67' in its proper historical space. Typically, insurrections have conspicuous leaders, organization, and a defined political agenda.

Arguably, Detroit 67' had none of these set pieces. Yet, the impulse to take on the armed might of the state was unmistakable. The insurgency defended territory taken from the police, formed sniper teams, set up ambush operations and launched assaults on hard targets and armed fortresses of state power.

The absence of conspicuous leaders and political agendas doesn't make Detroit less of an insurrection, but more so. Imagine the carnage on both sides if Detroit 67' was organized under a leadership group. Just as important, it was treated as an act of insurrection by the White House and the Pentagon.

Perhaps, Governor Romney summed up the long shadow Detroit 67' cast across the nation best when he said "Unless we take the proper course, this nation in the years ahead could be plunged into civil guerrilla warfare.”

For those seeking to locate Detroit 67' on America's historical arc, it closely rivals two watershed events. Neither insurrection was an modern urban rising, but their political intent and implications were quite similar; Shay's Rebellion in 1786-87 in Massachusetts provoked a newly formed nation to draft a federal constitution. Nat Turner's 1831 rebellion in Virginia placed the nation on an accelerated path to the Civil War.

To visit the corner of 12th Street and Clairmount today, where Detroit 67' began, underscores the effort to entomb the historic rising. In fact, there is no 12th Street today. It was renamed Rosa Parks Boulevard, after the dignified civil rights warrior whose defiant stance against segregation kicked off the historic Montgomery bus boycott and the civil rights movement across the south.

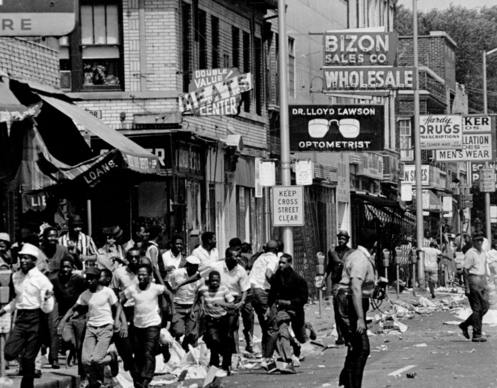

In 1967, 12th Street was a bustling commercial strip. By day, shoes stores, beauty shops, cleaners, clothing stores, pharmacies, bakeries, hardware stores, photo studios and optometrists shops bristled. By night, after hours joints hummed, street hustlers, small time gamblers, and prostitutes plied their trades. Elements of the Black middle-class, factory based working class and low income residents shared the same community space. That's all gone.

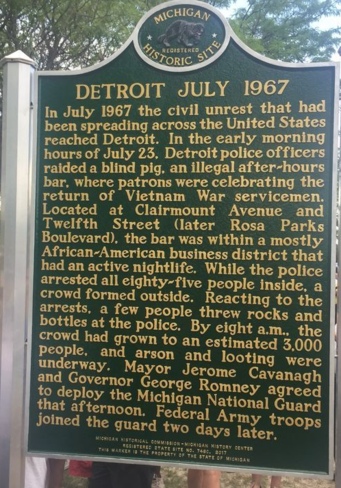

In a small green space adjacent to Clairmount and the former 12th Street, now sits Gordon Park. It was the site of the 50th Anniversary commemoration of Detroit 67. The service was led by former U.S. Congressman John Conyers, who at that very location on July 23, 1967, unsuccessfully tried to persuade Blacks to drop their rocks an bottles and go home. At the dedication, an ugly cheap green "historical marker" was installed.

The commission declared that no name would be assigned to characterize the events that happened there. They lied. The marker was titled "Detroit, July 1967." The first sentence reads "In July 1967, the civil unrest that had been spreading across the United States reached Detroit." Later, the marker states "Detroit's civil unrest that began on 12th Street lasted four days until July 27." So there you have it, Detroit 67 was officially a "Civil Unrest." It's one more example of what happens when history becomes "lies agreed upon by scholars." After all, when it comes to Detroit 67, few dare call it insurrection.

On July 28, 2017, National Public Radio published an article titled "Detroit 67' There's Still a Debate Over What to Call It." Uprising, civil disturbance, riot, rebellion or social unrest. The five days of tumult in Detroit have been called many things, but few dared to call it what it was: insurrection.

A half-century later, the specter of Detroit's uprising continues to haunt the ruling powers who crushed it. Since then, they've tried to close the book on this signature event by redefining its place in history. It's not going to happen.

Long ago, Detroit's Black community rejected the insulting attempt to label its revolt a "lawless riot" or a "race riot." Over time, "rebellion" emerged as a more acceptable alternative, imparting a level of political justification for violence directed against an unjust state of affairs. But even this term of art fell far short of capturing the totality of the moment.

That's because what happened those five historic days in July 67' was more than a rebellion (an act of violent resistance against authority). Something extraordinary went down in Detroit that set it apart from the other 200 Black upheavals that rocked America's cities in the 1960's.

That "something different" was how a spontaneous revolt quickly passed over into "armed insurrection." The violent resistance to police brutality that exploded on 12th Street on the morning of July 23, had escalated into a conscious armed offensive against government forces by nightfall. First, with rocks, bottles and Molotov cocktails. Then, with guns and rifles, the insurgents drove the Detroit Police and Michigan State Police from its "liberated zones." On the first day of the rising alone, the Detroit Fire Department attempted to respond to 259 alarms, some while taking incoming sniper fire.

What can't be lost sight of, is that within the initial chaos, looting, and burning of buildings, there was a state of open warfare. Once it was clear that the revolt was spreading across the city, the insurgents had no illusions about the lengths the Detroit Police Department would go to end the revolt. Decisions were already being made by the insurgents about taking the fight to the Tower (the government). They were right.

On July 24, less than 24 hours after the 12th Street raid, Governor George Romney (Mitt Romney's father) had already deployed the National Guard. At a 3:01 a.m. news conference, Romney warned that "fleeing felons are subject to being shot at." That statement was interpreted by the National Guard and the Detroit Police as a green light to "shoot to kill" whoever they deemed a felon. When Romney made his statement there were no reports of Blacks being killed by the Detroit Police. By the end of the day on July 24, nine (9) Blacks had been killed by the DPD.

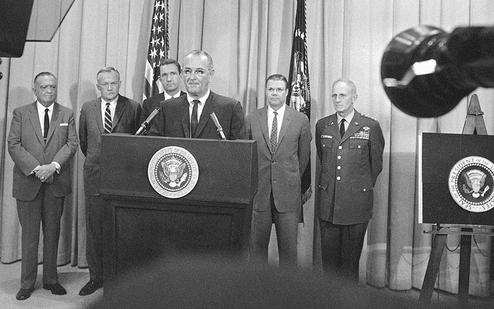

In response to the unprecedented level of the uprising, on July 25, President Lyndon Johnson went on national television after midnight, saying "Law and order have broken down in Detroit, Michigan." Flanked by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, Johnson signed the "Insurrection Act of 1807." The act authorized the use of U.S. "armed forces to fight an insurrection in any state against the government." An "open phone line" was activated between the Pentagon and Detroit. Smashing the insurrection moved to the Situation Room of the Defense Department. Detroit became America's first city since the Civil War declared to be in a "state of insurrection." U.S. armed forces would be garrisoned on its soil to quell the uprising.

July 23, 1967 - Sunday mornings meant one thing: church. That Sunday, unlike others, I was glad to go because we had just gotten a new car--a long shiny Buick Electra 225, with power windows and a drop top. The People of a Darker Hue called it a "Duce and a Quarter," a euphemism for a Black man's Cadillac. For Blacks who moved up and out, there were always three reasons to return to the old neighborhood, church, the beauty shop or the barbershop.

We lived in a mostly white and Jewish middle-class neighborhood on Detroit's Northwest side, littered with synagogues and Catholic schools. It was a fifteen minute drive to Metropolitan Baptist in our former all Black neighborhood. We were a few blocks from the church when my mother spotted a church deacon running towards our car frantically waiving his hands. She quickly pulled over and stopped the car. I remember him stepping down off the curb-a balding sixtyish man in a dark suit-wiping sweat from his forehead with a stiffly creased handkerchief. My mother rolled down the window and asked why he was so far from the church. "Ms. Brooks," he said "you can't get to church this morning. The Negroes are burning down everything."

Bewildered, by his response, my mother, ever the curious school teacher asked what was going on. The deacon, looking slightly exasperated politely said "I don't know Ms. Brooks, but it started early this morning, and it ain't stopped. They're even shooting at the firemen trying to put out the fires."

My mother thanked the deacon and told him to be safe. He turned and hustled back down the street looking for other churchgoers. My mother pointed our new car northward and we headed home. It was 10:00 in the morning.

Little did we know that what was first called the "Detroit Race Riot " had started at 3:30 that morning, after the police raided a “blind pig” (an unlicensed, after-hours bar). Ironically, the second floor haunt was located next to an office suite rented by a civil rights group called the United Community League for Civic Action. Outside the office building at the corner of 12th Street and Clairmount, as police officers began arresting late-night party goers, hundreds of angry residents of the area called Virginia Park buffeted police cars and paddy wagons with rocks and bottles.

By 5:00 a.m., as police hauled off the last group arrested at the raid, Molotov cocktails were being hurled and storefront windows smashed. By 8:00 a.m., three thousand people had massed on 12th Street. Looting had started and reinforcements from other precincts were called in. By the time Gov. George Romney (Mitt Romney's father) was called, the first fires were spreading. From that point on, there was no turning back.

In 67, our Congressman was the young John Conyers, one of the few Blacks in Congress in D.C. I met him in 1965. He came to my elementary school and invited me to speak at an assembly about the Vietnam War. It was the first of many rants I would give over the years.

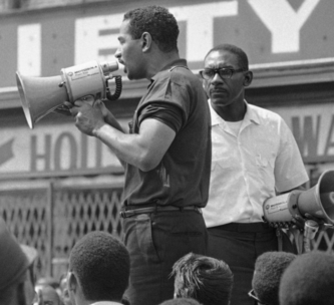

July 23, 1967 - 9:30 a.m. - Congressman John Conyers tries to cool out the crowd on 12th Street. They listened, they jeered and finally they threw rocks and bottles at his entourage.

Over a five-day period from July 23-July 27, Detroit's Black community was confronted by a combined occupying force of 20,106 government troops (8,128 Michigan National Guardsman 46th Infantry Division), 2,137 Michigan Air National Guard, 4,782 U.S. Army troops from the elite units of the 82nd Airborne and 101st Airborne Divisions, 277 U.S. Army Command and Support, 4,782 U.S. Reservists deployed to Chandler Park and the Michigan State Fair Grounds and 360 Michigan State Police. This combined force augmented 5,000 Detroit Police officers. The city was transformed in a full spectrum war zone: helicopters, tanks, armored personnel carriers, jeeps and 50 caliber machine guns abound.

Not intimidated, the insurgency dialed up its attacks despite overwhelming force. As the street violence spread, 2,498 rifles and 38 handguns are reported stolen from local stores. Over the next two days the insurgents created a record unmatched by any other urban revolt of sustained armed assaults on police stations, National Guard and U.S. Army special forces units.

On July 24 the Detroit Police 7th Precinct at Mack and Gratiot, came under heavy sniper fire. In the center city area, 40 National Guardsmen were pinned down for hours under extreme sniper fire at Henry Ford Hospital. The 5th Police Precinct was besieged overnight until the National Guard arrived the morning on July 25. On the same day, a police patrol wagon transporting machine guns came under attack by sniper fire at Hazelwood and Lawton. Again, on July 26, heavy exchanges of gunfire were reported between snipers and National Guard at Lycastle and Charlevoix. Sniper attacks at Fairview and Goethe on Detroit's east side were also reported.

The battlefield casualties of the insurrection were high. Forty-three people were killed, 33 were Black and 10 white. According to reports filed, 16 Blacks were killed by Detroit Police Officers. The three people killed at the "Algiers Motel Incident", by the DPD was a summary execution. Eight blacks were killed by the National Guard, including a four-year old girl. One black man was killed by a U.S. Army Airborne paratrooper. U.S. Army troops were supposedly under orders from the White House not to use live ammunition unless authorized by their commanding officers. The majority of Blacks killed were unarmed looters.

To understand how different Detroit's rising was from every other American revolt, it's useful to compare it to the 1992 Rodney King "Riots" in Los Angeles. Sixty people died in that rebellion, 17 more than died in Detroit. Of those 60 deaths, 35 of them died from gunfire, less than Detroit. However, only 10 people were killed by law enforcement officers and the California National Guard, compared to 27 in Detroit. This fact statistically underscores the nature of the deadly street warfare in Detroit between the resistance and forces of the state.

July, 23 Early Sunday Afternoon - On 12th Street, the community is out in full force

July 25, 1967 - President Lyndon Johnson announces he's invoking the "Insurrection Act of 1807" to deploy elite units of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Units to Detroit. He is flanked by Dept. of Defense Sec. McNamara & FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

About 9:30 that Sunday morning, Conyers came down to 12th Street to try and calm things down. With bullhorn in hand, he urged the disenchanted to return to their homes, and let the system work to correct police abuses. He was greeted by jeers, rocks, and bottles and asked to leave--a request he quickly acceded to.

That Sunday afternoon after returning home, we began seeing footage of the rising. I sat mesmerized, watching the grainy black and white film clips of people smashing windows and breaking in stores. Others moved down the streets with shopping carts filled with televisions and other electronic devices. I remember my mother shaking her head, as if she was in a state of suspended disbelief. It was all very surreal. The "rioters" looked like they were having fun.

In those days, my father was a Special Education teacher. Every summer he took some of his students camping in the wilds of Kensington Park, about 30 miles from the city. Hearing the news, he rushed back home. Later that evening, from our front yard, we could see smoke billowing against the sky to our south.

The rising had reached Fenkyl and Livernois, just a mile from our home. We didn't know it then, but that's as close as it would come. That night, Mayor Cavanagh slapped a curfew on the city. I remember my father cursing because gasoline sales were suspended. Luckily, we had gone grocery shopping that Friday, because reports were coming in about sniper fire all over the city. Store owners bolted their windows and refused to open. Others stores were overrun and the shelves were bare.

Still, we didn't realize how serious things were until President Johnson announced the U.S. Army was coming to Detroit. On my block some of the older brothers talked about how "some serious killing" was getting ready to jump off. Roger, a precocious 16 year-old said "That's not just the Army, that's the 82'nd Airborne that's coming. You know what they call them? Death from the sky," he said in a tone of lethality. "They're the ones killing all those people in Nam." We respected Roger. His level of cool was such that he didn't have to say Vietnam, just "Nam."

I asked if these "Airborne dudes" were as bad as the "Big Four." Anyone Black with an ounce of street smarts in Detroit knew about the "Big Four." They were units of four very large, plain clothed white cops. They rode in large black unmarked 4-door Dodge Fury's. They rarely spoke. They really didn't arrest people; besides there was no room to put prisoners in their cars. They specialized in beating down Black men. They were legend. Even the toughest brothers wanted no parts of the Big Four. Roger said the 82nd would eat the Big Four for lunch. That's when I knew whatever was going on a couple miles from our safe haven in Northwest Detroit, was going to be a deadly affair.

Over the next few days, the looting and burning slowed down but the killing went on. When it was all over, the next Sunday, my father took me and my sisters for a ride through the war zone. Whole streets and sections of the city were burned out. It looked Dresden, circa World War 2.

Just like the TV news clips we had watched the past few days, hastily painted "Soul Brother" impressions were painted on storefronts everywhere. Many of the black-owned businesses survived the burnings, others did not. Along the streets, I remember how slowly Black people moved, staring at the ruins of charred homes and businesses. It was as if they were in a state of suspended animation beholding the destruction they had wrought with their own hands. Two years later, many of the mom-and- pop grocery stores would be rebuilt. But all the Jewish shop keepers were gone. They were replaced almost overnight by the burgeoning Arab communities and merchants springing up all around Detroit.

We asked our father if he could drive down Grand Boulevard to see if the Motown Records headquarters was still there. To our relief it was still standing. Motown was the beating heart of Black Detroit and Black America in the mid-sixties. But the music that came out of Motown in the months that followed would not be the same. The Temptations and Supremes songs like "Stop in the Name of Love" and "My Girl" would be replaced by militant, socially conscious tunes like "War" and "Ball of Confusion."

My mother wanted to see the statue of Jesus Christ, whose face, hands and feet were painted Black during the rebellion. To our astonishment there was Jesus on the front lawn of the Sacred Heart Seminary, his outstretched jet Black hands beckoning sinners to his bosom. It was an absolutely shocking site.

Two months later, some whites repainted the statue, but the Archdiocese directed that the communities' verdict be upheld. It was painted Black again.

As the hot summer of 67' faded to fall, we returned to school in September. I don't recall in all my years since, witnessing a bureaucracy respond so fast to the social fury of the moment. We had two new classes never offered before. Contemporary Affairs, was a class with no textbook. Students and teachers brought magazines and newspaper clippings to discuss in group sessions. As a 7th grader, I also had my very first Black History class at Hampton Jr. High. My sister's high school (Mumford) was one of the first in the country to walk out over the Vietnam War.

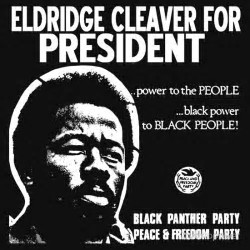

In 1968, I headed the Hampton Jr. High mock campaign team to elect Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver for President on the Peace ad Freedom Party ticket. We edged out the Democratic Party nominee Hubert H. Humphrey by three votes.

That mock election, was symbolic of how fast America was changing. For me, the innocent wide-eyed Cub Scout, Detroit 67' had changed everything.

Black Jesus at Detroit's Sacred Heart Seminary

I grew up in Detroit. I remember that hot summer day in July 1967; who could forget?

Sunday mornings usually meant one thing: church... Not that Sunday."

The Editor, Black-Nationalism.com

NewBlackNationalism.com

Detroit 67' Why None Dare Call it Insurrection