NewBlackNationalism.com

BLM 2.0

What We Believe

Contact Us

Reparations

Fanon Forum

Afrofuturism

BLOG

Introduction:

01.28.2022

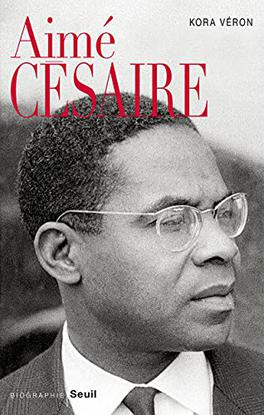

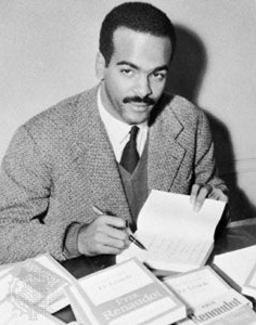

Following ten days of CIA interrogations and emergency surgery for late-stage leukemia, Frantz Fanon died in December 1961, in Bethesda, Maryland. Four days later The Wretched of the Earth was published, prompting the French government to ban the book and seize copies from Paris bookstores. When Aime Césaire passed in 2008, the Negritude movement’s 94 year-old co-founder was interred in a state funeral presided over by French President Nicolas Sarkozy. He called Césaire a ‘great humanist and poet.’

Logic and history concur that the substantive difference between Fanon and his former teacher was one of revolution versus accommodation. “I condemn any idea of Antillean independence” said Aime Cesaire. "I only know of one single France. That of the revolution. That of Toussaint Louverture.” But the philosophical polarities between these two Martinicans: between Fanonian theory and Negritude’s sprawling oeuvre, was anything but a simple equation. Rather, it was a thick and complex intellectual confrontation with profound ramifications for the future.

Fanon and the Negritude Question revisits Frantz Fanon’s extended polemic with the Negritude movements' leading intellectuals. In many respects their discourses framed the quintessential philosophical arguments that dominated the African diaspora’s anti-colonial awakening.

From 1949 to 1961, Frantz Fanon crafted a critique of Negritude’s foundational constructs. In doing so, he bequeathed to future generations a cipher more so than a philosophical blueprint that responded to the problematic Césaire put before his friend Léopold Senghor in the 1930s: “Who am I? Who are we? What are we in this white world?”

New Black Nationalists assert Fanon’s rejoinder to Césaire on the construction of the Black subject emerged as the locus of the philosophical dispute with the Negritude movement.

Fanon’s skirmish with Negritudists traversed a galaxy of issues and produced an algorithm that hummed to the source codes of being, identity, culture, and epistemology. Leavened with the grammar of Fanon’s psychoanalysis of the colonized, NBN posits that Fanon's critique of Negritude in the aggregate created a coherent and unified philosophical system.

The cryptology of the Fanon/Negritude exchange is rich. Arguably, Negritude’s philosophical polyglot probed, embraced, or foreshadowed virtually every intellectual strand enrooted in the African diaspora experience. Thus, NBN holds that Negritude’s centrality to the African diaspora intellectual tradition merits critical reevaluation. This is especially important in the United States, where Negritude's African and Caribbean roots relegated it to the periphery of Black thought.

Within America’s settler state, New Black Nationalists argue that the derivative philosophies of the following intellectual currents were addressed substantively or tangentially by the Fanon/Negritude arguments.

Negro/American Double Consciousness– W.E.B. DuBois, M.L. King, Civil Rights

Black Marxism – African Blood Brotherhood, Blacks/CPUSA, Cedric Robinson

Marxist Nationalism – Black Workers Congress, League of Revolutionary Workers,

Pan-Africanism- The Garvey Movement

Pan-African Socialism – All African People’s Revolutionary Party

Cultural Nationalism – Maulana Ron Karenga – US (United Slaves) Organization

Religious Nationalism – Nation of Islam, Black Moors, Black Hebrew Israelites

Afrocentrism – Molefe Asante

Afropessimism – Jared Sexton and Frank Wilder

Radical Black Nationalism – Malcolm X, RAM, Black Arts Mvmt., Black Panthers

Nation-State Black Nationalism – Republic of New Afrika, New Black Nationalists

Negritudists were well versed in the sciences of Vitalism, Marxism, Pan-Africanism, Créolité, Caribbeanness, Black Surrealism, liberal republicanism, and nationalism. In the lycées and lecture halls of the French academy, they were bred by the Fourth and Fifth Republics to become the native elites of the home colonies and exemplars of French cultural assimilation policy.

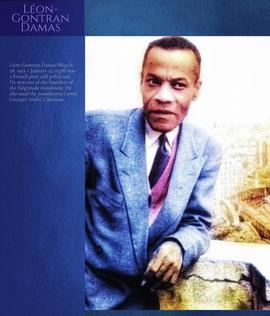

It’s no accident that Black Francophone intellectuals like Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, Leopold Senghor, Leon Dumas, Paulette and Jane Nardal, Rene Maran, Suzanne Lacascade, Alioune Diop, Suzanne Cesaire, Edouard Glissant, and Achille Mbembe exercised disproportionate influence in the African Diaspora’s philosophical solar system.

Philosophy was a baccalaureate requirement in France’s educational system, and the national pastime for French elites and the popular masses. They consumed the works of Descartes, Rousseau, Sartre, Camus, Foucault, and Derrida with brio. French Empire also took its "mission civilisatrice," to enlighten its beleaguered colonial natives seriously. The production of Black intellectuals whose anti-colonialism maintained French identity was a strategic consideration of the Caribbean and Africa Desk at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

New Black Nationalists contend that the writings of scientific racism theorist Count Arthur de Gobineau also had a decisive impact on the development of Black Francophone philosophy in the arenas of art, culture, and aesthetics.

Negritude's fealty to French Identify was also shaped by a seismic event that remains seared into the Black Francophone collective memory. We speak of the Haitian Revolution--the world's only slave uprising that led to the founding of a nation-state ruled by non-whites. Despite Toussaint Louverture's brilliant leadership in defeating Napolean Bonaparte--the planet's most formidable military general--he never lost his sense of French identity, thereby creating a legacy that exist to this day in the Antilles.

Louverture's 1801 constitution for a free Haitian state unconditionally banned slavery. Seeking to rid Haiti of French colonial rule, Louverture's constitution read "Slaves cannot exist in this territory and servitude is forever abolished. Here, all men are born, live, and die, free and French.” While Louverture believed Haiti could forge an autonomous republic, he concluded independence wasn't desirable or possible in the short-run and sought to rebuild Haiti under French protection. After forcing the French to call for a peace treaty, Toussiant's misplaced trust in Bonaparte to honor the peace agreement led to his imprisonment and death shortly thereafter in France.

When Cesaire exclaimed "I only know of one single France. That of the revolution. That of Toussaint Louverture.” he evoked Louverture's decision not to break from France but lead a Black autonomous republic within French Empire. Cesaire's appropriation of Louverture to justify Martinique's path of becoming an overseas department when independence was achievable without bloodshed was a rancid act of opportunism. Lest we forget General Jean-Jacques Dessalines defeated the French on the battlefield a year after Louverture's death to consolidate Haiti's revolution. The Louverture Predicament continues to cast a long, contradictory, and anxiety-filled shadow across the Caribbean. For all his revolutionary heat and writings, Fanon was silent on the historic armed Haitian revolutionary struggle and the legacy of Toussaint Louverture.

Fanon's Engagement with Negritude

Fanon’s opposition to Negritude first surfaced in two plays, The Drowning Eye and Parallel Hands, written in 1949. Fanon’s autobiographical plays omitted any reference to Negritude’s circular concerns that defined Francophone’s vibrant cultural milieux in Paris. His criticism was anything but subtle. Quite the opposite, it signaled Fanon’s intent to shift the philosophical battlefield from surrealism, poetic knowledge, and vitalist African cosmology to Sartrean-inspired existential phenomenology.

In stark contrast to his plays, Fanon’s publications of Black Skin, White Masks (1952), and The Wretched of the Earth (1961) launched a frontal assault on Negritude, concentrating its fire on the issues of language and Black identity.

At the Congress of Negro Writers and Artists in Paris (1956), Fanon argued that colonialism was expanding its cultural offensive against Blacks, Jews, and Orientals. He postulated that increasingly racism’s evolving technologies were less rooted in the canard of biological difference and were migrating toward the deculturation of the Third World. Fanon’s Algerian national liberation experience convinced him an expanded field of vision was needed. It was Richard Wright’s questioning of how Blacks from the United States fit into Senghor’s “single African personality,” schema and why traditional African culture folded under colonial rule, that upended the 1956 conference.

In the 1959 Writers and Artists conference in Rome, Fanon answered Wright’s 1956 entreaty on the African personality. He contended that authentic culture was by definition national culture. Deprived of the twin pillars of nation and state, Fanon said cultures perish and die. Challenging notions of African supranational organizations and continental thinking, Fanon averred that “National liberation and renaissance of the state were the preconditions of the existence of culture."

Joining Algeria’s National Liberation Front and taking over as Editor of its El Moudjahid newspaper in Tunisia from 1957-1959, Fanon’s criticism of Negritude shifted from philosophical issues to Algeria’s escalating liberation war against France. Placing Senghor and Césaire in the dock, Fanon brought them to book for their refusal to support the Algerian revolution.

After becoming the FLN’s Ambassador to Africa in 1960, Fanon began forging ties with Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Guinea’s Sekou Touré, and the Congo’s Patrice Lumumba among others. Shotly thereafter, the French government made two unsuccessful assassination attempts on Fanon’s life.

The Fanon-Negritude quarrel unfolded against the backdrop of Third World emancipatory independence movements reaching their acme. Bogged down in Vietnam’s liberation war, and losing its grip in Algeria, unrest in West Africa and the Caribbean Lesser Antilles threatened to collapse France’s Fifth Republic and imperial empire. The stakes of the Fanon/Negritude disagreement were of real consequence.

Negritude’s Genealogy:

Negritude’s modernist roots resided in metropolitan Paris in the 1920’s. Its patron saint was Haitian anthropologist Anténor Firmin. Ironically his 1885 work, On the Equality of Human Races, proffered a stinging rebuke to Count Arthur de Gobineau’s white supremist writings. Gobineau famously suggested that “The Negro is not a pure and simple brute, for within the narrow confines of his cranium there exist indications of grossly powerful energies.”

Consonant with France’s hierarchical traditions, the Lesser Antilles were the “old colonies” first occupied by the French in the 1630’s. Black Antilleans were regarded as “civilized” compared to colonized Blacks in West Africa, and Arabs for whom the French reserved a special place in hell. Educated Black Antilleans of Martinique, Guadeloupe, Haiti, and Guinea served as colonial French administrators and civil servants in Paris, West Africa, Madagascar, and Réunion.

It was this educated class that coalesced in Paris in the 1920s, that began pressing the French government to grant republican rights and citizenship to its colonized Africans and Antilleans. Their sage advisors and master teachers: Haitian Dr. Leo Sajou, writer Maurice Satineau of Guadeloupe, Martinican administrator Jean Price-Mars, novelist and colonial administrator Rene Maran, Louis Achille, the famous Claymont Salon hosts and writers Jane and Paulette Nardal, constituted a formidable republican circle of activists dominated by Martinicans. They published journals, magazines, and newspapers that established a political platform to launch and sustain an African diasporic intellectual movement.

The Parisian Francophone circle also established intimate ties with a retinue of Harlem Renaissance cultural luminaries that began migrating to Paris in the 1920s. This transcontinental network ran well into the 1950s. The infusion of Harlem Renaissance works and the interaction of the two artistic communities brought the themes of Black pride and cultural autonomy to life in Paris. Among the Harlemites who lived in Paris between the 1920’s and 1950s were Alain Locke, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, Chester Himes, Richard Wright and James Baldwin.

Like Fanon, the educated Francophone colonized elite, grew up believing they were French until they migrated to France. There, they discovered they weren’t French because they were Black. It was a rude awakening and at the same a catharsis of sorts. Out of this void or racial chasm, Negritude’s ascent conjured the rise of a new Francophone Negro.

Incubated in the student dormitories, sidewalk cafes, and toney solons on the Left Bank of Paris's Black arrondissements, Negritude came of age in the 1930s. Impatient with African and Antillean elites’ failure to secure republican reforms in the colonies, Negritude emerged as a radical student-led poetic and literary cultural nationalist revolt.

Its young leaders advocated a saucy anti-assimilationist, anti-colonial, pro-African heritage gumbo adorned in Pan-Africanist grandeur. In 1935, Negritude’s founders: Leon Damas, Amie Cesaire and Leopold Senghor published L'Étudiant Noir (The Black Student), that put the youth movement on the map.

Despite the philosophical diversity of Negritude’s leaders, NBN asserts that in the 1940’s, Negritude evolved into a distinct school of thought. Negritudists synthesized its antecedent Panafrican discourses into distinct philosophical formulations. Its taxonomy of constructs included Black identity, language, being, aesthetics, culture, and epistemology.

Damas’s 1948 anthology Negro Poems Written to African Airs appeared in French colonial verse expounding themes of racism and Western colonial culture. It was banned by the French government. In 1939, Cesaire’s famous work Notebooks of a Return to the Native Land penned in surrealist poetics and metaphor was published. Senghor’s An Anthology of the New Negro and Malagasy Poetry went to print in 1948. Its preface, written by Jean Paul Sartre, that praised and belittled the work in the same sentence immediately raised Negritude’ profile across Europe and within the French Empire. Along with Presence Africaine, Negritude's marquis cultural and political journal and Black publishing house, Negritude expanded as the preeminent Black intellectual behemoth.

Negritude's rise as a house of philosophy occurred despite its remarkable diversity because its commonalities outweighed its differences. Indeed, Cesaire inveighed against the notion that Negritude was a philosophy by saying, "Négritude, in my eyes, is not a philosophy. Négritude is not a metaphysics. Négritude is not a pretentious conception of the universe. It is a way of living history within history: the history of a community whose experience appears to be … unique, with its deportation of populations, its transfer of people from one continent to another, its distant memories of old beliefs, its fragments of murdered cultures."

In this instance we are prepared to believe Cesaire fell victim to own words, because his writings that shaped the Negritude world were intensely philosophical if nothing else. Nevertheless, New Black Nationalists argue that the common markers that bound Negritude as an unstable but distinct philosophical school including the following:

- Preservation of French identity.

- Upholding French as the official national language.

- Adopting an idealist conception of the Hegelian binary white master/black slave dialectical relationship of reciprocal recognition of each other’s humanity through the mediums of art, language and traditional African religion.

- Creating Black subjects in accordance with the scientific racism theorist Arthur de Gobineau’s who stated, -- the artistic accomplishments of any civilization are fundamentally derived from “Negro blood.”

- Perpetuating a masculinist culture

- Creating theories of knowledge and being from aesthetic constructions. Cesaire fashioned an epistemology from surrealist “Black poetics of knowledge,” and Senghor from African art.

- Opposition to achieving state sovereignty and political independence from France in exercising self-determination.

On the Construction of the Black Subject

As previously stated, Fanon’s response to Césaire and Senghor’s construction of the Black subject centered his philosophical dispute with the Negritude movement. This discourse was a continuation of W.E.B. Dubois’s challenge to the founding fathers of scientific racism theory: Thomas Jefferson, Arthur de Gobineau, and Fredrich Hegel.

Scientific racism theory posited that reason ruled the world. Reason was the energy and substance guiding philosophy as a reflective mode of thought based on logic. The logic of reason produced clarity and truth. Hegel theorized that when humans obtained this self-actualization were they “free subjects," participating as members of a state and contributing to its intellectual and moral development.

Hegel’s white supremist views insisted no other modes could produce these profound truths, therefore whites were justified in enslaving African heathens who lay outside of civilization and the modern nation-state. In fact, Hegel suggested it was only through slavey and Africans close proximity to whites, that the pre-linguistic Black race could advance to become free subjects.

Like Hegel, the Frenchman Arthur de Gobineau believed whites were superior to Africans and Asians. But Gobineau didn’t regard Blacks as non-humans existing outside of history. Nor did he support slavery and colonization, as did Hegel. Quite the opposite, Gobineau stated, “The artistic accomplishment of any civilization is fundamentally derived from “Negro blood.”

Speaking of Gobineau, Cesaire said “But of all our influences, the most determining seems to have been that of the ethnologists and their predecessors Gobineau, Levy-Bruhl and above all the romanticism of Leo Frobenius.” Senghor and Cesaire interpreted Gobineau’s musings on "artistic accomplishment of any civilization" to mean Negritude's cultural revolt was not just another artistic movement: it was superior to any artistic endeavor whites ever created. Moreover, Senghor and Cesaire's interpretation of Gobineau remarks opened the door for Black poetry, prose, painting, music, sculpture and especially language as the mother's milk of civilization, to be placed in the service of creating a Black subject.

Senghor on the Black Subject:

Leopold Senghor’s construction of the Black subject dismissed European claims that Africa never possessed a civilization or logos by arguing that African people and African civilization existed prior to Africa’s contact with Europe and Enlightenment’s “age of reason.”

Senghor theorized that “Negritude was founded on the notion of vital force that is pre-existing, anterior to being constitutes being. God has given vital force not only to men, but also to animals, vegetables, even minerals. Negritude defines the collective Negro-African personality, and that personality is characterized by its sense of rhythm and its capacity to be emotionally moved. Negritude is the sum total of the values of the civilization of the African world."

Fanon did not deny the existence of an ancient African civilization. He thought basing Black subjectivity on an archaic subject that no longer existed was folly and a step backward in a modernizing world. Nor as a philosophical materialist and humanist did Fanon believe in religious and cosmological theories, mysticism, ancestor worship, or animism. “In no way” said Fanon “must I strive to bring back to life a negro civilization that has been fairly mis-recognized. I will not make myself a man of any past. I do not want to sing the past at the expense of the present and my future.”

In response to Senghor’s claim of a cosmology-based "universal African identity, Fanon inveighed “My skin in not the repository of specific values. Negritude thus came up against its first limitation, namely, those phenomena that take into account the historicizing of men. “Negro” or “Negro American” culture is first and foremost national, and that the problems for which Richard Wright or Langston Hughes had to go on the alert were fundamentally different from those faced by Leopold Senghor or Jomo Kenyatta.”

Cesaire on the Black Subject and Language:

Cesaire’s Black subject, on the other hand, was the post-colonial Creole, created out of the synthesis of the African, French, and Martinican cultural and historical experience. In Cesaire’s construct it is language, not Senghorian cosmologic creation or European reason that serves as the transcendental signifier.

Cesaire argued that “Whether I want to or not, as a poet I express myself in French… I have always striven to create a new language one capable of communicating the African heritage. I wanted to create an Antillean French, a black French that, while still being French, had a black character.... This is why I am much more interested in poetry than prose, and this insofar as the poet creates his language, while in general, the prose writer uses language."

Cesaire admits his Creole subject is a subject in a state of decay, partly because the subject cannot fully express itself in language, thus one has to be created. Cesaire’s new language will be Antillean French or Black French. Either way it will be French, and it must reflect an African heritage.

Cesaire was simply unable to break with French identity as its association with language demonstrates. So too, his notion that he can create a language that compels subjectivity is fantastical. In the first chapter of Black Skin, White Masks, on The Black Man and Language Fanon says, “Language is essential for providing us with one element in understanding the black man’s dimension of being-for-others, it being understood that to speak is to exist absolutely for others…The more the black Antillean assimilates the French language the whiter he gets-i.e., the closer he comes to becoming a true human being”

Whereas Fanon says language is “one element in understanding the black man’s dimension of being-for-others,” Cesaire sought to create a whole subject on the edifice of language. Fanon pointed out that while "Creole was a popular language spoken by most Martinicans it was destined to become a relic of the past once Martinique’s most underprivileged had access to public schools and libraries."

In a not so cryptic reference to Cesaire, Fanon inveighed that “For the poets I’m talking about here it’s not a question of their turning themselves into Antilleans by borrowing a language that is devoid of any external influence, whatever might be its intrinsic qualities, but a question of asserting their personal integrity faced with Whites who are steeped in the worst racial prejudice.”

Cesaire’s hypocrisy and betrayal on the Creole language question is stunning. As the island’s political leader, his embrace of Martinique becoming an overseas department of France made French its official language. Unlike Haiti, that made Haitian Creole its official language along with French, Cesaire did no such thing. Today, Martinique remains a department of France. French is spoken by 90% of its people.

It was the brilliant Martinican philosopher Edouard Glissant and friend of Fanon, who observed that “Creole is the language of the people, Creole is not the language of the nation. The official language, French is not the language of the people. That is why the elite speak it so correctly. We can also state, based on our observation of the destructively nonfunctional situation of Creole, that this language in its day-to-day application, increasingly becomes the language of neurosis. Screamed speech becomes knotted into contorted speech, into the language of frustration.”

Further Glissant made a critical argument about language that related to Fanon's theory that culture develops in proportion to national consciousness. "A national language" said Glissant "is the one in which a people produce.” Since Martinique is crippled by an absence of self-sustaining productivity, it is a community without a national language. Language not only reflects but enacts the power relations in Martinican society. Neither French nor Creole are the true languages of the community.

Cesaire's Poetic of Knowledge

The centrality of language to Cesaire’s Negritude's construct extended beyond its role of infusing his synthesized Creole with self-actualization. To accomplish this self-actualization, Cesaire sought to develop a new epistemology of poetic knowledge as an alternative form of rationality to scientific knowledge or instrumental reason.

In France, Cesaire, Senghor, Negritudists, and their fellow Communist Party travelers, were smitten with surrealism as visual and written art forms. Critical of Europe's sterile culture that offered no resistance to World War, the Nazi holocaust, and America's atomic bombing, Surrealism distorted everyday images and grammar to create alternate realities and tap the recesses of the subconscious.

Elaborating on the difference between "scientific knowledge" and "poetic knowledge," Cesaire posits that "Science offers a view of the world. But it is summary and superficial...the essence of things escapes it...scientific knowledge, numbers, measures, classifies, and kills. To acquire it, man sacrificed everything: desires, fears, feelings, and psychological complexes."

Instead, Cesaire summons "poetic knowledge," whose origins he describes in the following passage. "Man was never closer to certain truths than in the first days of the species when he discovered fear and delight, the shivering newness of the world: attraction and terror, trembling and wonderment. In this state of fear and love and climate of emotion and imagination, man made his first, most fundamental, and decisive decisions."

"In the modern era," Cesaire argues "this original enchanted relationship to the world has survived only in the sacred phenomenon of love and the nocturnal forces of poetry. In all times the poets always know. "

At the end of the day, Cesaire asks that we honor the poet as a clairvoyant voice, a seer endowed with special cognitive insights that can guide the incomplete Creole to full subjectivity.

Asked about his vision of "poetry as prophecy" and a "primitive African belief in poetry", Cesaire responded by saying, "That's it, but just primitive, not necessarily African! The prophet! What interests me is primitive Greek poetry, primitive Greek tragedy. Moreover, whether Latin or Greek, I only appreciate them in their primitivity... At bottom, we can glimpse that Roman civilization or Greek civilization, at their start, were not very far from African civilization. All that was gained through reason was lost for poetry. It seems to me that the surrealist conception of the image is the meeting point."

Perhaps Negritude historian Gary Wilder sums up Cesaire's poetics best in his book "Freedom Time." "Cesaire is less interested in challenging French colonialism by retreating into primordial Africanity than in identifying within European and Antillean history those unrealized revolutionary possibilities through which colonialism could be overcome and a lost primitive-poetic relationship to knowing and being recuperated. "

Senghor: Black Art as Aesthetic, Being, and Epistemology

Senghor's views on Negritude as a philosophy were entirely different from Cesaire's. Senghor insisted Négritude is a philosophy of African art: a Black Aesthetic if you will. “Négritude” he said, “as a philosophy of African art, is not to reproduce or embellish reality but to establish the connection with what he labeled the sub-reality that is the universe of vital forces.” Borrowing from Jane Nadal’s “rules of rhythm.” Senghor not only links philosophy to art, but music to being. “What is rhythm? It is the architecture of being, the internal dynamism that gives it form, the system of waves it emanates toward the Others, the pure expression of vital force. Rhythm is the vibrating shock, the force that, through the senses, seizes us at the root of being. The ordering force that constitutes Negro style is rhythm.”

One of Senghor most controversial statements concerned his formulation of Negritude as an epistemology. Of Négritude Senghor said, “Emotion is Negro, as reason is Hellenic. European reason is analytical by utilization, Negro reason is intuitive by participation.” For Senghor “Negro-African” epistemology is a form of Black cognition that transcends European distinction between object and subject. Senghor’s Négritude considered art as knowledge and aesthetics as epistemology.

Senghor's construct on Black art that combines being, aesthetic, and epistemological consideration raises an interesting point about Negritude's impact on Black liberation movement in America's settler state. While its early genealogy was linked to the Harlem Renaissance, one instance Negritude influenced the 1960s Black Liberation movement was Senghor's theories on ancient African civilization. They were adopted by Maulana Ron Karenga's Cultural Nationalist US Organization. The organization was guided by Nguzo Saba, the "seven principles of African Heritage" that Karenga described as "a communitarian African philosophy."

Karenga was a force in the revolutionary Black Arts Movement. His dictum that "Black art must be functional, collective, and committing, " and "Black art must expose the enemy, praise the people and support the revolution," had purchase among revolutionary artists we dubbed the Hand Grenade Poets. In a similar way, Afrocentrists associated with Molefe Asante in the 1980s and 1990s asserted traditional African culture was informed by its history that was more "circular than linear: more cooperative and intuitive, and more closely integrated with the spiritual world of gods and ghosts."

Some Closing Thoughts

Negritude's inability to broadly influence the intensely philosophical Black Arts Movement in America's settler state is illustrative of philosophy's diminished role in the Black intellectual tradition.

Fanon was a popular figure in most radical quarters of the Black Power Movement and the Black Panther Party. The Black Panthers likened America's Black ghettos as oppressed colonies of U.S. imperialism that required a liberation war like Fanon's description of the Arab Quarters' squalid "bidonvilles" in Algiers. Fanon proclaimed the peasants and lumpenproletarian would lead the revolution, not the working class. The Black Panthers adopted the same position about the "brothers on the block."

The Panthers like many in the Black Liberation Movement were inspired by Fanon's uncompromising revolutionary politics but didn't grasp the importance of Fanon's philosophical arguments. The nationalists who didn't take up Pan Africanism in one form or another gravitated to Marxism-Leninism. Black Arts Movement co-founder and poet Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones) who evolved to "Marxist "higher order thinking," summed up his BAM experience by concluding; 'It is still my contention that we were revolutionaries, albeit saddled with the weight of nationalism which does not even serve the people." How pathetic.

Understandably, Cesaire's capitulation to French imperialism and Senghor's corrupt Socialist Party that plundered Senegal, while imprisoning and murdering protesting students and workers, didn't inspire enthusiasm to critique Negritude's philosophical oeuvre.

But if success is the measure and depth of our intellectual curiosity then Fanon's international popularity as a revolutionary philosopher cannot be explained. Algeria's National Liberation Front succeeded in overthrowing French colonialism, but in less than a decade turned into a murderous authoritarian one-party state. Lamentably, Algeria followed that path as Fanon predicted in The Pitfalls of National Consciousness in The Wretched of the Earth.

Independence came to eighteen African countries in 1960. Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, Zimbabwe and South Africa won their liberations struggles by the early 1990s. Arguably, none of these liberation struggles has stood as an incandescent beacon of Fanon's New Humanist republic. Fanon's detractors continuously point to these "facts" as proof of the failure of Fanonian theory. But with each new chapter, like Grenada's New Jewell Revolution and Burkina Faso's revolutionary movement, we come closer.

There is an enduring lesson to be learned from Fanon's intellectual combat with the Negritude movement. Despite his difference along philosophical and ideological lines, Fanon lauded Negritude as a necessary tool that helped disalienate and decolonize Black minds. Fanon stated when he learned Blacks worked silver and gold 2,000 years before being discovered by White civilization, it allowed him to gain a valid historical perspective that Blacks were not primitive or subhuman. Although Negritude's philosophy of Black pride was a potent counterbalance to assimilationist tendencies, it was ultimately an inadequate response to an imperializing culture presenting itself as a universal worldview.

Fanon accepted that Négritude was part of a dialectical movement that pointed toward human emancipation because he understood race could not be human destiny. In the same way, Fanon critiqued, Marxism, Freudian psychoanalysis, Hegelian dialectics, Sartrean existentialism, and Merleau-Ponty's phenomenalism as deficient because they all neglected to take race into account. Instead of discarding these Western theories, he extracted their revolutionary kernel, bent them, and placed them in the service of his revolutionary project.

Fanon held that the French language was a proxy for "self," just as the Algerian colony or Martinique's overseas department was a proxy for the "Other." He believed language teaches the colonized to express themselves in an oppressive language system as a speaking object. But when the Algerian National Liberation Front, stopped boycotting the use of French in 1956, and deployed it as a lingua franca to unite its diverse resistance, including non-Arab speaking people, Fanon supported the measure.

To return to the nexus of Fanon's quarrel with Negritude, Fanon rejected the idealist Hegelian master/slave binary of mutual recognition of the others humanity. As Fanon said, "The master sought not recognition but work from the slave, whilst the slave wanted to be like the master."

Fanon insisted the Black man could not achieve subject status by assuming white identity. Nor could he simply write, speak, or through performative acts, will himself into existence as a subject respected by the white man. The reversal of the totalizing colonial violence, terror, and psychological disorders visited on Black bodies and minds required meeting violence with violence and overthrowing colonial rule.

Fanon postulated that Antillean consciousness was not actualized as Hegel's Phenomenology theorized. Martinique and Guadeloupe acquiring overseas department status conjured the illusion of freedom without the struggle for it. Antilleans were the beneficiaries of imperial largesse but failed to achieve recognition from colonizing French colonialists because as Fanon argued, real freedom and real recognition is acheived when one stands up and looks the enemy in the eye.

Overcoming inferiority complexes and exploitation is a question of desire: it is to desire freedom more than imitating the white subject. Action is the Black logos. Action, violence, and revolution constituted the materialist, not the idealist, dialectic initiating the creation of a new Black subject.

For Fanon, the colonized had a choice to make. His Sartrean-inspired existentialism insisted their exploitation and oppression was not a pre-determined and fixed reality. Individuals and people had the power to control their own destiny. They could continue to accept abuse and domination or take responsibility for their future and define their own existence. What Fanon forcefully injected into the Afro-Caribbean intellectual and political tradition was a new sense and theory of being. But Fanon's ontological theory wasn't enough to overcome Antillean loyalty to French identity.

In The Origins of Fanon's Philosophy, New Black Nationalists asserted that until Negritude's emergence, "Philosophy operated as the handmaiden of the political and ideological struggle in the Afro-Caribbean intellectual tradition." The same can be said of the Black intellectual tradition in America's Settler state.

Like Cesaire's hybrid Creole, DuBois's Black subject was the synthesis of the Negro and European-American cultural, historical, and psychological experience. It was manifested in his theory of double-consciousness. Unlike Cesaire and Senghor, DuBois's counterdiscourse was not an argument from the colonial Other-from-without threatening French Empire's outer boundaries. Dubois's argument was against Thomas Jefferson's scientific racism theory that casts Blacks as a malevolent and dangerous Other-from-within that posed an existential internal security threat to America’s imperial order. Led by its Talented Tenth, DuBois argued Blacks could attain true self-consciousness and contribute to the American Experiment as equals.

Toward the Adoption of a Fanonian Philosophical System

In February 2021, New Black Nationalists committed to engage in a one-year critical reading of Frantz Fanon's corpus of works and adopt his theories as our guiding philosophical system. On February 28, 2022, our series of thought papers covering Fanon's writings on women, nationalism, nation-building, violence, Marxism, and New Humanism will be completed. As Fanon's writings on philosophy center our adoption of Fanonism as our philosophical system, three papers were drafted that are solely dedicated to philosophical questions.

The Origins of Fanon's Philosophy framed the argument that Fanon's works constitute a coherent philosophical system. It located the origins of Fanon's writings in the Afro-Caribbean intellectual tradition, as opposed to a European tradition. Fanon's Quarrel with Negritude asserts that notwithstanding all its diverse and conflicting constructions, Negritude constituted a distinct school of philosophy. The Fanon/ Negritude arguments across an expansive spectrum of ideas, especially the construction of the Black subject created a baseline in which subsequent Creolite, Antilleanite, Afrocentrism, Afropessimism, Afropolitanism and Black Atlanticist philosophies are derived.

In February 2022, Fanonism and the Black Nationalist Experience in American Empire will conclude our series. Our final paper will explore how Fanon's writings comport with developing our analysis of the prospects of winning state power in the 2020s and building a Black-led republic.

Frantz Fanon's Quarrel with Negritude

Achille Mbembe

Edouard Glissant

Adenor Firman

Suzanne Cesaire

Leon Damas

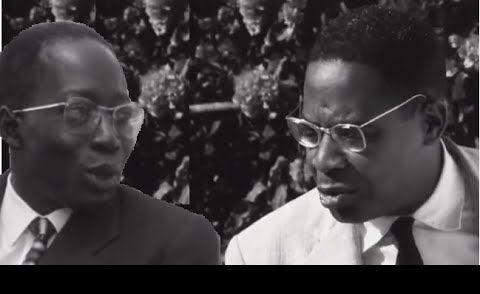

Leopold Senghor

The Nardal Sisters

Aime Cesaire

The Fanon Arguments No. 7

Leopold Senghor Aime Cesaire